Probably the most frequent and difficult questions I’ve been asked are about where I’m from… I have an indefinable accent, a name that’s hard to pronounce and I look white, but not ‘white enough’ for some people in the city where I live (Montreal, Canada). My identity is always a little astray from the categories that preoccupy the societies in which I have lived.

I am the first in my family to be born in the ‘promised land’ and to grow up in a city as divided as Jerusalem – a division that compelled me to seek my place within a community. As my matrilineal ancestry is not Jewish, but Armenian, I do not benefit from certain rights due to the Orthodox Jewish laws followed by the State of Israel. I gave three years of my life to the Israeli navy, suffering from trauma to this day, while the majority of Israel’s Orthodox Jewish community never served a day in the army.

A famous quote from Israel’s General Elazar Stern says that “the people build an army that builds a people”, which became the backbone of identity building in Israeli society. And that’s how I naively thought I’d find my way, hoping to fit in for once. But even after my service, my identity, or lack of it, was the reason I was shunned. My close relatives reproached me for not ‘loving’ Israel because I wasn’t Jewish, among other accusations. If anything, I care deeply about Israel when I denounce the government for its apartheid regime and call for the uprooting of Jewish supremacy and the embracing of some of the values on which Judaism is founded: “The stranger who dwells with you… you shall love him as yourself” (Leviticus 19:34). It was then that I despaired of finding myself in this country.

I returned to Canada as an adult (I also grew up here between the ages of 8 and 14). Here I was gradually exposed to the slow process of ethnic cleansing of this country’s indigenous populations, who today are receiving at best a few stipends for creative projects and land acknowledgment announcements at public events to disengaged audiences. I felt that as an immigrant, I had more privileges than the native people of this land. The culture of sweeping everything under the carpet is very much alive, but today, the truth behind this “land of the free” is being gradually unearthed. In recent years I started volunteering at a houseless shelter where the majority of the clients were indigenous. I heard their stories and saw firsthand the systemic racism and police brutality they face. I started connecting the dots, understanding the similar mechanics of oppressive power systems that infuse their fabricated ideas of normalcy, determining who and what is part of their society. After a few more initiatives, including fundraising and film projects intended to raise awareness of the scars of Canadian society, among other things, I also began to feel that I was unconsciously working on healing my own scars. My efforts were directed at amplifying the voices of those who were unheard, in contrast to the time when, in the Israeli army, I contributed to a system that erased the Palestinians.

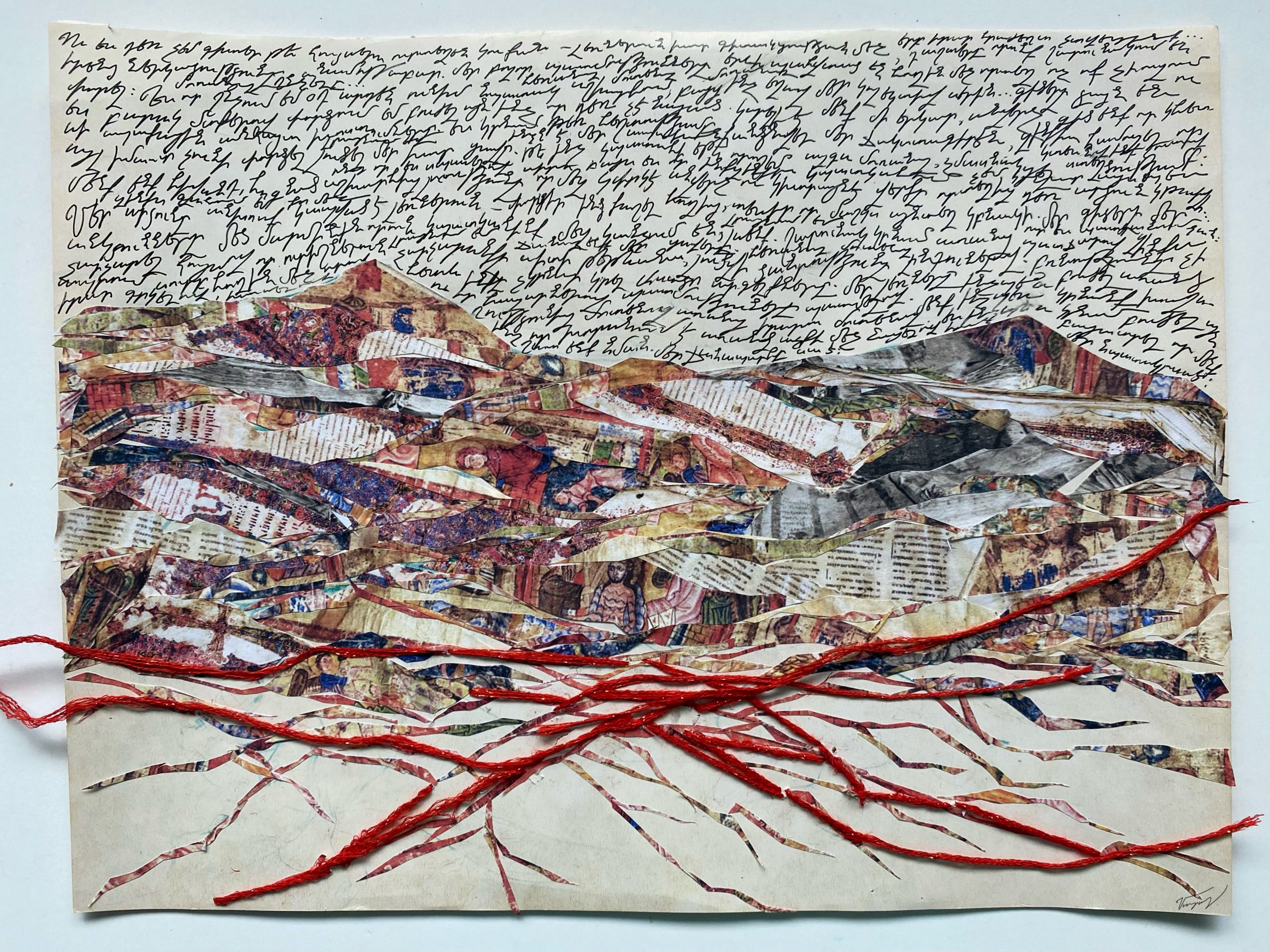

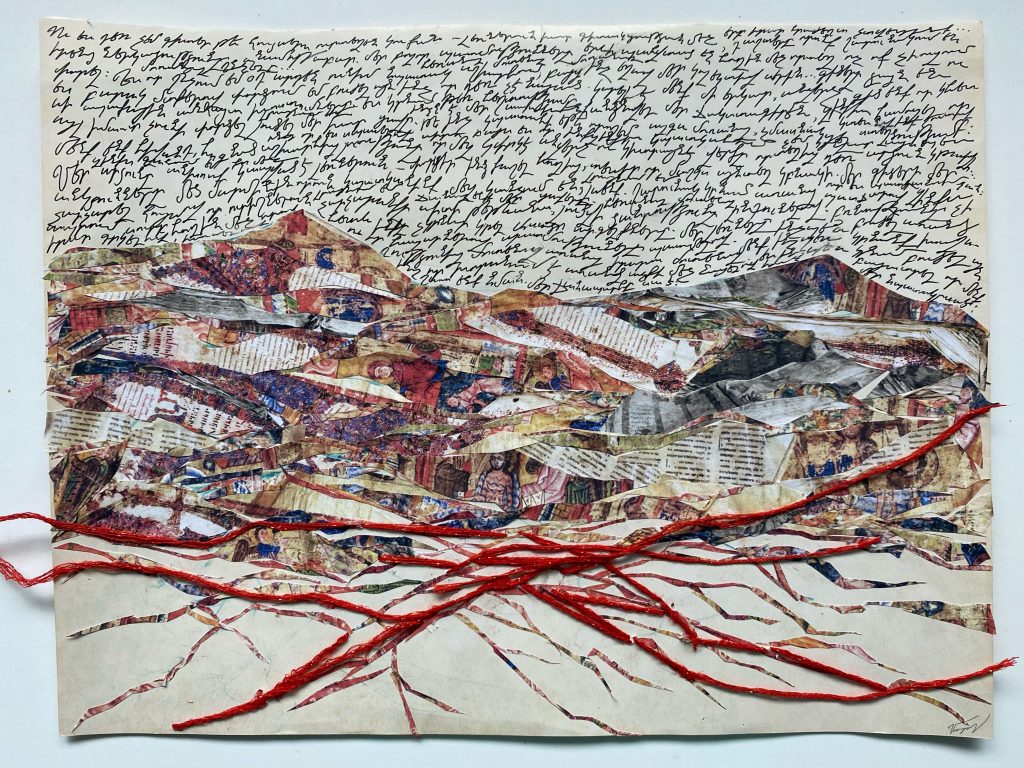

My lived experience under overt and veiled systems of oppression, and the complex make-up of my identity allows me to be sensitive to and have a birds-eye-view on these systems because I never really fit in. In recent years, I’ve started to get closer to my Armenian roots, which make up more than half of my ancestry. This exploration came to the fore during the Artsakh War of 2020 (better known as the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War). When I attended a protest in my city and learned about the provenance of my family, some of whom come from Artsakh, I felt something quite unusual. I felt an inexplicable sense of belonging that I’d never experienced before. I felt that the pain of the Armenians as a nation touched me to the very depths of my being.

Ever since, my instinct has been to cherish this ‘newfound’ identity, especially when there is an immediate threat to Armenian sovereignty. I feel called to speak out and strive against the reality that Armenians, particularly Artsakhis, face. It is clear, to some at least, that the blockade of the Lachin corridor and the genocidal acts perpetrated by the Azeri regime are means of keeping the soil of the region ablaze so that countries of the former USSR depend on Russia to have the upper hand. It is also true that European governments are turning from one dictatorial regime to another to source their oil—which in actuality is just repackaged Russian oil. This exposes not only that dependence on fossil fuels is twisted, but also that the sustenance of the people of Artsakh is not even close in terms of priorities or conditions for trade for the international community.

But these facts are easily overlooked by most media outlets and international organizations, and this reality is not ‘trendy’ enough for social media either. I am now closely following the tactics used by the dictatorial regime of the President of Azerbaijan. Attempts to bend history in Azerbaijan’s favour, as well as using articulate representatives and politicians to spread disinformation both through the education of Azerbaijani society and on international platforms, are chillingly reminiscent examples of my experience in Israel, where ignorance is used as a political tool to instill hatred, terror and a sense of revenge.

And what better way to challenge my sense of belonging than to witness how the Israeli government is playing a decisive role in the deterioration of the Armenians’ right to exist— sending substantial quantities of arms to Azerbaijan under the guise of defence exports. I grew up in the shadow of the atrocities of the Holocaust, seen as a justification for the existence of the country where I was born, while today its regime supports efforts to eradicate other groups, including my own mother’s people. What could be more repulsive? They say history repeats itself—well, that’s what I’ve learned from observing my identity when part of me belongs to a people who went from being victims to victimizers, and when my other half belongs to a people who are subjected to an offensive power that is striving to complete the Genocide of 1915. I recognize the similarity between the narratives I grew up around in Israel and Palestine and those that rise up in me today in the context of Armenia. But what always resonates with me the most is that true peace is never achieved at the expense of the freedom of others.

Today I mourn a place I’ve never seen, but just as I’ve never seen my heart, I know it’s an inseparable part of my being. I carry within me the trauma of my ancestors from Artsakh, but so do I carry their strength and this inspires me to keep voicing my truth with determination in the midst of all the hypocrisy. I have grown closer to myself.

Free Artsakh.

Yon Nersessian, Graz, Austria 29/09/2023