Consent has been the center of a lot of discussion lately, both within the Armenian community and outside of it. Though legal definitions of sexual consent vary from country to country, the Merriam-Webster dictionary defines it as “giv[ing] assent or approval.”1

Simple enough, right? Not exactly.

Let’s elaborate further on this definition by addressing the complexity of consent. The first step in this process is discussing what counts as consent, why and when you need it, and how it can improve sexual relationships so that everyone involved is comfortable, safe and happy. The second step is defining sexual harassment. In order to best clarify consent, we have to start discussing harassment as a whole, as well as the rape culture that perpetuates it. The third step is finding ways and resources to stop this behavior in its tracks.

What is consent? Why is it important?

Consent means that there is both an active and voluntary agreement to engage in any form of sexual activity with someone. It means that everyone involved is comfortable and willing to partake. It means everyone wants the encounter to happen.

Clarifying and discussing consent creates a mutually understandable, clear agreement about what you like and what you don’t like. It establishes boundaries and helps communication to thrive, ultimately creating a safe and enjoyable space for sex. It also plays a key part in the prevention of non-consensual sexual encounters.

How do I know I have consent? What if they didn’t say no, or didn’t protest?

It’s safe to say that we’ve all heard some variation of the phrase, “Well, they didn’t say no.” According to the University of Indiana, because “consent is active, not passive; silence, in and of itself, cannot be interpreted as consent.”2 Thus, consent can be expressed not only verbally, but physically as well. It’s crucial to both take into account someone’s words and to pay attention to someone’s nonverbal cues, body language and general demeanor.

Let’s think about some real life examples. If you’re about to hook up with someone who seems fidgety, wary or nervous, you should confirm consent. If you’re about to hook up with someone that is completely silent or unresponsive, you should confirm consent. If you’re hooking up with someone who tries to pull away during your encounter, you should confirm consent.

Silence, passivity, submission and even the lack of a “no” should not be considered as giving consent.3 Just because someone doesn’t say the word, “no,” it doesn’t mean that they’re saying the word, “yes.” This applies to all sexual activity – one must give consent every time, otherwise, it is considered sexual assault or rape. So, in order to grasp a better sense of how your partner is feeling, it’s important to learn how to read someone’s nonverbal cues and body language. Fremont College provides important resources on how to analyze body language, resources that can be used both in gauging consent and in gauging how someone is feeling in general.4

Reading someone’s body language does not mean assuming their consent based on what they are wearing or how they present themselves outwardly. It does not mean assuming someone’s consent based on their makeup, based on their occupation, based on their dress, etc. Reading body language to confirm consent and judging someone’s presentation are not the same thing. It’s not about how someone looks, how they dance, how they drink. It’s about an active and enthusiastic agreement to engage in sexual activity.

Sometimes, talking about consent can be awkward, but it doesn’t have to be. No matter how difficult, talking about consent is the best way to know that everyone is ok. Questions and phrases like, “Are you okay with this? We can stop if you want to,” or, “Let me know if you are uncomfortable,” are good starting points to a greater discussion. Communication and vocalization become easier the more you put them into practice.

I’ve hooked up with this person before. Doesn’t that mean we can hook up again?

Regardless of whether or not you’ve hooked up with someone in the past, or even if you agreed to hook up earlier but changed your mind, you are always allowed to revoke consent. This applies to all sexual encounters – in long term relationships, in marriage and in short term hookups. Just because you have a history with someone doesn’t mean you have to hook up with them again.

Under what circumstances am I unable to give consent?

There are multiple circumstances in which consent cannot be given under US law. If you are asleep or incapacitated due to alcohol, drugs, or a physical or mental condition, you cannot give consent. If someone is threatening you, forcing you or causing you significant distress, you cannot give consent. If you’re feeling peer pressured or guilted, you cannot give consent. In the United States, you cannot give consent under the age of 18 (in some states, the age of consent ranges between 16 and 18 years old). Under these circumstances, the encounter would be considered sexual assault or rape.

It can be easy to rely on legislation to understand and define consent. But it’s important to remember that consent can also be defined outside of the laws of the nation in which you live. Consent is about comfort, boundaries and safety – it’s not just about establishing an age at which you legally can’t give consent. It’s not just about following the laws on paper – it’s also about knowing how to read vocal and physical signs that show your partner’s desire to engage in sexual activity, and proceeding from there. It’s about establishing a basis for respecting one another, for having healthy relationships, and for fostering a safe environment to talk about sex.

Consent isn’t a bullet point list created by any single nation. Consent is a conversation. It’s communication. It’s the foundation for safe, enthusiastic and enjoyable sexual relationships.

What is sexual harassment? Why is it important that we address it?

Now that we know the details about consent, let’s talk about what occurs when you engage in sexual activity without your partner’s consent. There are many, often interchangeable, terms to describe non-consensual sexual activity. Some examples include sexual misconduct, sexual assault, sexual abuse, and sexual harassment. Under US law, each of these terms means something different, with their own varying penalties, but there exists a lot of overlap in their legal definitions. As we discussed above, we cannot simply rely on legislation to give us the full definitions of these crucial concepts, as laws on paper often fail to encompass the importance of sensitive topics such as sexual misconduct.

For the purpose of this article, we’ll be referring to non-consensual sexual activity by using the broader term sexual harassment, and we’ll be defining it by building much needed foundation on its basic legal definition.5

Sexual harassment is when someone makes unwanted sexual advances toward you, be it verbal or physical. It includes physical/verbal attacks of a sexual nature, unwanted touching/physical contact, online harassment, aggressive offhand comments, and more. Here are some examples of what sexual harassment looks like.

1. Sending explicit photos, emails, or texts without the receiver’s consent. Colloquially, we often refer to these photos as “nudes” or “dick pics.”

2. Making inappropriate or lewd jokes referring to sexual acts or someone’s sexuality.

3. Exposing oneself to someone who did not give consent.

4. Following someone around or invading someone’s personal space in an attempt to initiate sexual activity.

5. Asking invasive questions about someone’s sex life.

6. Touching someone without their permission.

It is critical to address sexual harassment as a whole. Victims of sexual harassment can suffer from significant psychological effects, including depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, weight loss or gain, nausea, low self-esteem and sexual dysfunction. They also experience work-related costs: from job loss and decreased morale, to irreparable damage in interpersonal relationships at work.6 Ultimately, sexual harassment has the potential to derail a victim’s life – mentally and physically.

What’s rape culture? How can we combat it?

Rape culture describes an environment in which sexual violence is not only pervasive, but is normalized by the media and in popular culture.7 Rape culture is sustained through the use of sexist language, the objectification of women’s bodies, and the glamorization of sexual violence. It creates an environment where, “it is acceptable to teach sexualized violence prevention as ‘don’t get raped’ instead of ‘don’t rape.’”8 Here are some examples of rape culture.

1. Trivializing harassment as “locker room talk” or saying that “boys will be boys.”

2. Using language that degrades or objectifies women (calling women whores, sluts…).

3. Victim blaming or using statements like, “they asked for it!”

4. Teaching young girls and women how to avoid being sexually assaulted as opposed to teaching young boys and men not to commit sexual assault.

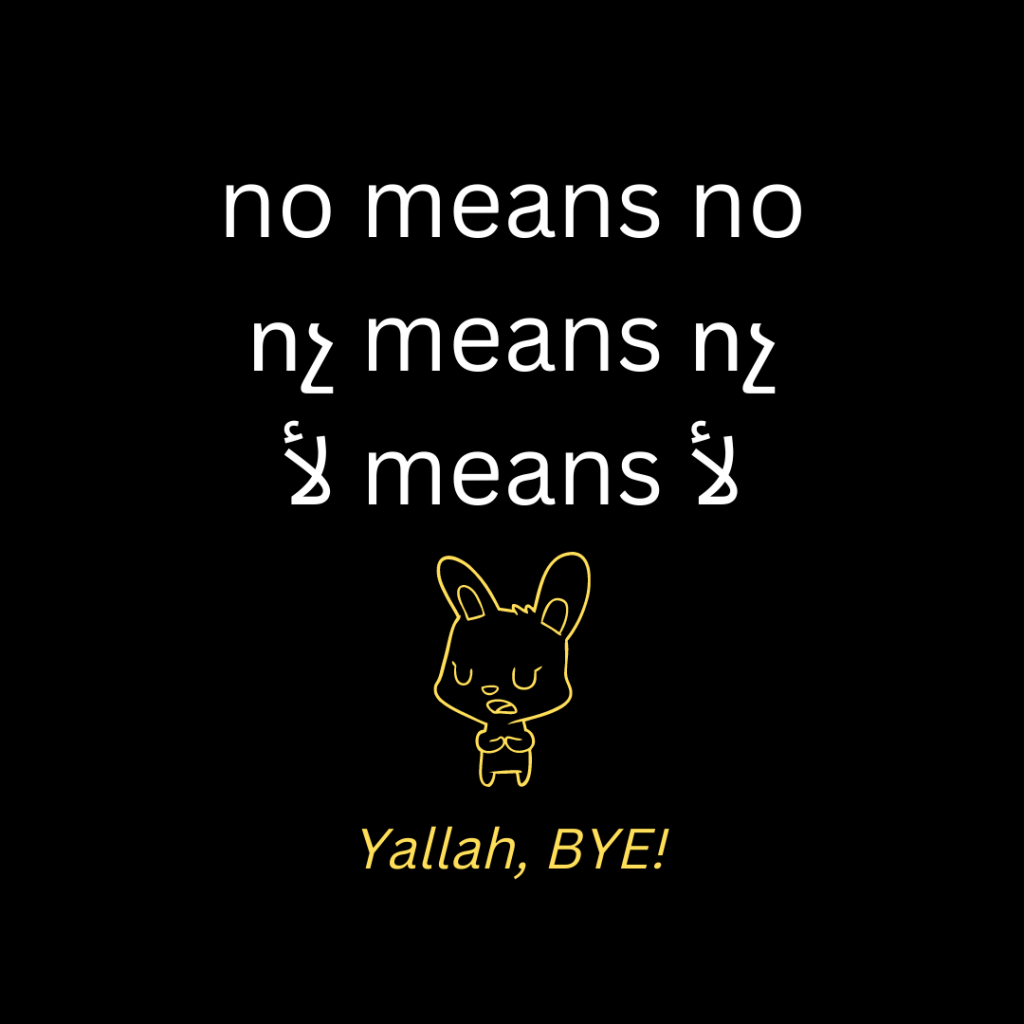

5. Tropes in film and media that assert that when a woman says no, she really means yes. Or, tropes that assert that when a woman says no, a man should continue chasing her until she utters the word yes.

Rape culture forces women to live in a world where they must take a personal responsibility to prevent themselves from being sexually harassed or assaulted. Women are taught to be careful about what they wear, who they talk to, where they walk, when they walk, what they drink, how much they drink, whether it’s dark outside, how many people they sleep with. Women are taught to take self-defense classes, to walk around with a taser or pepper spray, to hold their keys between their fingers, to check the back of the car before getting in the door…

And when the unthinkable does happen, despite the most stringent precautions, rape culture forces victims of sexual violence to live in a world where their experiences are undermined, their perpetrators unpunished, their truths unbelieved.

In 2011, The University of Surrey published a study in which researchers gave a group of men and women quotes from British men’s magazines, as well as excerpts from interviews with convicted rapists.9 Participants were asked to identify which quotes originated from the magazines and which quotes originated from the convicted rapists. Alarmingly, the participants couldn’t reliably identify which statements came from magazines and which statements came from rapists. They also rated the magazine quotes as “slightly more derogatory than the statements made by men serving time for raping women.”10

This is just one example of the way that mainstream media perpetuates rape culture. When it’s unclear whether a rapist uttered those words or a magazine printed those words, there is a huge problem. These men’s magazines, and other magazines just like them, are sold en masse to hundreds of thousands of men globally – they are consumed at extremely high levels. Media, as a whole, has normalized the degradation and sexualization of women all over the world. And women? Well, women are expected to just deal with it.

The responsibility to act morally always lies with the perpetrator. It is not a person’s responsibility to preemptively protect themself from being sexually assaulted.

How can we, as supporters of victims of sexual violence, combat rape culture?

On the most basic level, rape culture grounds some of its power in subconscious biases and assumptions, so even bringing awareness to it brings us one step closer to dismantling it.11 We can also avoid using bigoted or misogynistic language. We can call out those who are using this type of language or those who are making offensive remarks trivializing sexual violence. We can stop victim-blaming and urge all those around us to do the same.

More tangibly, we need to establish structured and well studied sex/consent education for everyone, not just young students in health class. We all have to take the time to understand the complexity of consent. Ultimately, this type of education is far more productive than teaching women the art of self-defense. If we teach respect, understanding, agreement and conversation about sex from the get-go, we can make a massive impact on the lives of so many people.

Invest in organizations that amplify the voices of victims and survivors. Establish zero tolerance policies for harassment in the spaces you exist in. Hold the utmost respect for the privacy, personal space and health of the people in front of you. Practice asking for consent and noticing the feelings and boundaries of those around you, whether you’re with a romantic partner, with friends, or in the workplace. By creating a culture of interacting with each other with active, enthusiastic consent, we can create spaces where everyone is happier, safer, and more connected.

1https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/consent

2https://www.usi.edu/sexual-assault-prevention-and-response/what-is-consent/

3https://www.usi.edu/sexual-assault-prevention-and-response/what-is-consent/

4https://fremont.edu/how-to-read-body-language-revealing-the-secrets-behind-common-nonverbal-cues/

5United Stated Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC): “Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature constitutes sexual harassment when submission to or rejection of this conduct explicitly or implicitly affects an individual’s employment, unreasonably interferes with an individual’s work performance or creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment.”

6http://www.equalrights.org/professional/sexhar/work/workplac.asp

http://www.stopvaw.org/effects_of_sexual_harassment.html

7https://www.marshall.edu/wcenter/sexual-assault/rape-culture/

8https://www.brandonu.ca/sexualviolence/education-prevention/rape-culture/

9https://jezebel.com/can-you-tell-the-difference-between-a-mens-magazine-and-5866602

https://abcnews.go.com/blogs/health/2012/01/03/mens-mag-or-rapist-study-claims-few-can-tell

10https://abcnews.go.com/blogs/health/2012/01/03/mens-mag-or-rapist-study-claims-few-can-tell

11https://www.vox.com/2014/12/15/7371737/rape-culture-definition