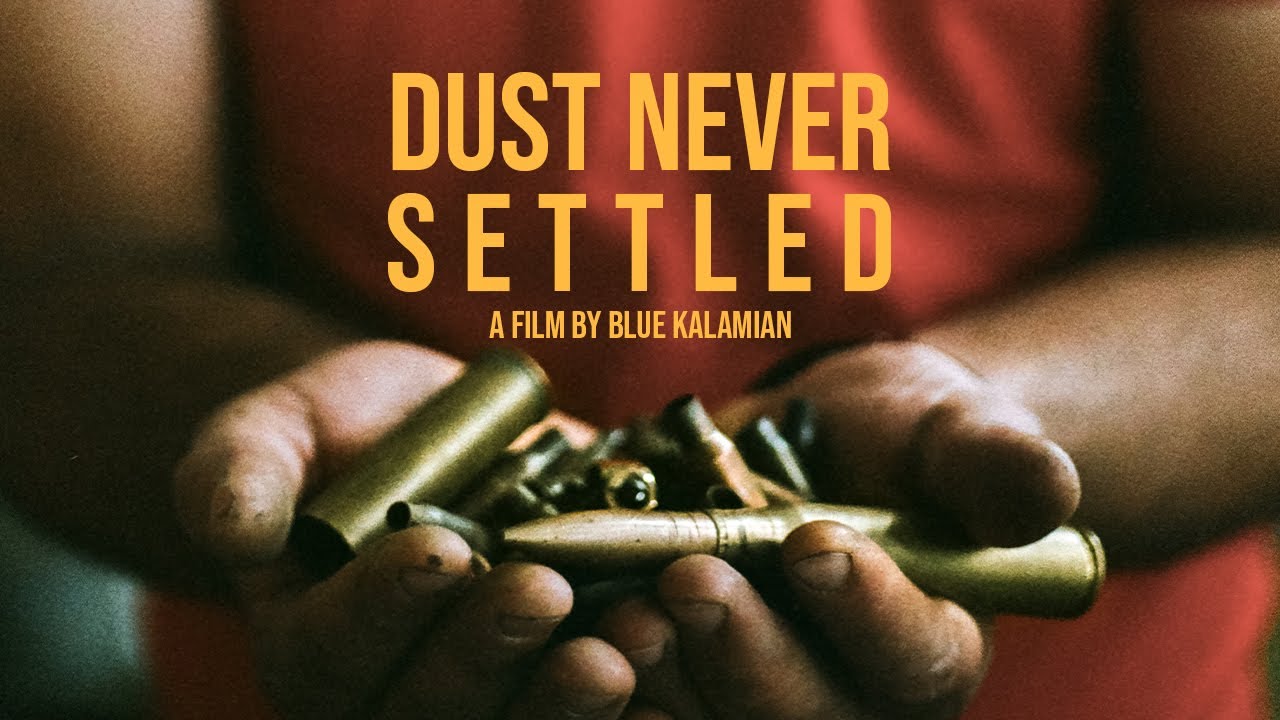

Just over one month ago, the Armenian community watched in horror as Azerbaijan launched brutal attacks on Artsakh, finally completing the ethnic cleansing of its entire indigenous population. We remain heartbroken and scared as we continue to see genocide perpetrated on a global scale, while the military invasion of Armenia looms. In these dire times, it’s more important than ever to amplify the stories of the people who have been affected by the 2020 Artsakh War, and its ramifications continuing to unravel. In September, just before the last wave of attacks began, I interviewed Blue Kalamian, whose 2022 documentary film Dust Never Settled followed soldiers wounded in the 2020 Artsakh War and the families affected. Although the situation has already evolved, the stories Kalamian shares, including his own, and the insights gained remain pressingly relevant today.

Araxie Cass: Can you tell me a bit about the inspiration and process behind the film?

Blue Kalamian: When I studied film in San Francisco, I focused mostly on fiction. But I started finding a love for documentary in my last year at university. I had just started wading into documentary work when COVID hit and everything stopped. You couldn’t organize film shoots, so I sat for most of COVID very frustrated because I had ideas and things I wanted to do, and suddenly I didn’t have a job.

When the war started, I started to get these thoughts of I want to help, I want to do something. At the time, all that I really felt I could do as an Armenian from America, from far away, was to spread awareness. I was doing the same thing as everybody else: posting on social media, donating money, sharing fundraisers. But it never really felt like enough.

Once it ended, it was almost worse because it didn’t feel like anything we had done was enough. So if I were to say if there was any inspiration for the film, it would be that feeling. Like no amount of donating money, or posting on social media, or protesting, or whatever felt like it was actually doing something. I had this internal frustration, and I think a lot of us Armenians felt that way.

When I got the opportunity to go, I remember my first thought was: I can’t train the soldiers or be a diplomat or a doctor. I’m not trained in these things, but I do know storytelling. I do know how to create moving images, both literally and figuratively – pictures that make you feel something. So I thought if there’s anything I can do, it’s go and share those firsthand stories with people who wouldn’t otherwise see them.

I saw the film as a way to get the firsthand experiences of people to the cellphones, the computers, the front page of somebody else’s phone – so that they could witness the war for themselves. So they could see what’s actually going on. Because it’s not just a sad mother crying and some soldiers shooting at each other. It’s not just videos on Instagram. It’s a real thing that’s affecting a lot of real people, people who are not so different from us in America.

AC: After you made the decision to film in Armenia, how did everything come together?

BK: I remember it was the day before my birthday and my best friend called me and basically said, “I’m not gonna be able to come hang out for your birthday because I’m going to Armenia.” His cousin was an orthopedic surgeon who was performing surgeries on a lot of soldiers who were wounded by artillery blasts, some high-caliber snipers and drones. He said, “We need extra hands, we need help.” My friend was an EMT, so he was going to assist his cousin in the operating room. I was, of course, very proud. I said “That’s amazing man. I’m really happy for you,” and I kind of joked like, “Man I wish I could come. I’ve been thinking about how badly I want to make something about this and I just wish I could come.” And he asked, “Why don’t you?” And I didn’t have a good reason not to. I know it sounds like it’s scripted or something, but I swear I just sat on the phone, and I was just asking myself, why don’t I? Why not?

This was November 13th, so the war had ended 4 days earlier. And so the next day at noon, we boarded a flight and we came out here to Armenia. I really didn’t have any network or resources here. The only thing I had was my friend, and his friend who we were staying with. On day one we went to the hospital. It was a little bit awkward at first to try to get people to understand what I was doing there because I wasn’t a medical professional and I didn’t want to get in the way or intrude on anybody. But once people got comfortable with me, it became clear that they wanted to share their experiences.

Other than that, there wasn’t a lot of preparation. It was literally just get up and go. When I was here, though, I was able to connect with Birthright Armenia. I told them about what I was trying to do, and that I would really like to go to Artsakh and film firsthand and try to get stories from people who were still there. Up until that time, I had just interviewed soldiers in the hospitals and families who had come to Armenia as refugees. They hooked me up with a media company. I did some work for them, and then they were the ones that helped me get to Artsakh. They also connected me with a couple of other groups, like an orphanage that was taking in Artsakhtsi children who had lost their parents, or mothers who had lost their husbands as well.

AC: Was that your first time coming to Armenia?

BK: Yeah. I stayed for one month and then I went back. Then in April 2021, I came again to do Birthright properly. I did that for four months and then when I finished, I just stayed here.

AC: What has that whole process been like, from coming to Armenia for the first time to now living there?

BK: It’s been life-changing for sure. I’ve never been able to pinpoint an exact moment when such a huge change occurred in my life. I love it here. I really, really love it. I’ve been here two and a half years and I still feel like there’s so much I haven’t done yet. But I’ve also done so many things that I love. There’s beautiful nature. I love hiking, camping, and backpacking, so Armenia is full of diverse environments to explore. Plus, there are a lot of cultural things that I never had growing up.

My dad’s really proud to be Armenian and although my mom’s not Armenian, she pushed us to embrace our Armenian heritage. She’s the one who pushed us to go to Armenian school when we were younger. But even so, both my parents grew up in America. My family came basically directly from Turkey to America a couple of years after the Genocide. So I feel like I longed for certain things including the language. The food, I had, ‘cause my grandma would make some great Armenian food. But I didn’t speak Armenian, I didn’t know about our holidays, I didn’t even know about the country’s history that well.

It’s been really great being here and seeing new perspectives on life and on things that I thought to be true. I see a lot of people who are supporting Armenia from abroad and they have all love in their hearts and that’s amazing – but I also see that there’s a lack of mutual understanding in certain areas. And it’s been interesting to be here; obviously I didn’t grow up here so I don’t have the same perspective as people who did, but I definitely see things differently now that I’m here every day. And I also see where a lot of diasporans are coming from because I’ve been a diasporan my entire life.

AC: That’s interesting, what you mentioned about having both perspectives of being a diasporan and living in Armenia. Are there any disconnects you’ve noticed?

BK: There definitely are. The important thing to understand, I think, is that Armenia is not paradise. There are a lot of people who come here and they love Armenia. They love the nature and how old our churches are and how deep-rooted our history is, but they only see a small part of it. It’s hard to explain how much you’re missing by not being here all the time. And I’m not saying everyone should move here either. I’m just saying that you really don’t see everything unless you’re present for it.

So I think a lot of the disconnect I’ve seen on both sides is really misunderstandings – a lack of walking in the other’s shoes. But it’s not that black and white either. I see a lot of locals who are so thankful for the diaspora. During the war I remember I was asking one of the soldiers in the film about the diaspora, and he said that if it wasn’t for the diaspora, he wouldn’t be here. His unit was given some materials that were fundraised for by the diaspora, probably boots or food or jackets or something like that. But on the other hand, I think that a lot of locals feel like the diaspora isn’t always fighting for what’s best for Armenia as a country because they don’t understand; they haven’t lived here.

And on the flip side, I think a lot of diasporan Armenians really want to help, but they’re thinking of things in a worldview that is very shaped by wherever they come from. And I cannot stress enough how nuanced everything is — the politics, this war, the geography, borders — this is a very, very unique area of the world. You can’t just take solutions from elsewhere and implement them here.

There is a disconnect between the two, but at the same time, I think there’s a lot of love. It’s like any family: you love them but sometimes you just cannot see eye to eye. You want the same outcome, but you disagree on how to get there, and both of you are kind of right, you know? And that’s how it is, our dysfunctional Armenian family on a macro level.

AC: I know you’ve been showing the film at a number of film festivals. What kinds of responses have you gotten, both from Armenian and non-Armenian audiences?

BK: I think the biggest pride for me was that Armenians were really into it and that people didn’t think that it’s just another video, because a lot of journalists did come here and report.

I think Armenian people felt that my film was more personal. It was less about the history of the situation and the politics of everything, and more just about what war does to people, and what people have had to go through. And that’s really what I wanted it to be. I really wanted to craft it into something that was more poignant and directed at the effects of war because it’s not just like an action movie with a bunch of shooting. It lasts a lot longer than that. It lives in people.

I’ve also received a lot of good feedback and good reviews from non-Armenians. A lot of the non-Armenian people I know reached out to me to say, this is great, I had no idea that it was like this. For that I think that it was a success; it got people who weren’t paying attention to at least know that it was going on. Once it started going out to festivals, I think that it definitely got more of that positive attention. All of the awards we won were for non-Armenian festivals. So that was cool, that non-Armenians were seeing the value in it and saying, “This is something that people should be paying attention to.”

AC: I did appreciate that there was less of the action or war story and much more of the personal stories of people and the effect the war had on them. What are some things that you hope people get out of this film when they see it?

BK: I really want people to be interested enough in the situation and invested enough that they continue to pay attention. I think that’s another reason I wanted it to be personal; there are a lot of different characters in the film that one might be able to relate to. There’s 18-year 18-year-olds who are younger than my youngest brother who are still living with their injuries. They’ll never be 100% like they were. Not only that, but they’ve seen and sometimes done unspeakable things that they can’t process properly. There are mothers who are less concerned about fighting a war and more concerned about protecting their children and living life in the place that they grew up, that they love. And men who have seen multiple wars and are hardened fighters and yet at the same time are sweethearts. They don’t let that stop them from being who they are, and that’s a different kind of strength that I’ve never witnessed firsthand before.

So I think that if anyone can relate to any of these types of people, they might see that this person is not so different from myself. And it might not do anything on the grand scale, but at least if my film had anything to contribute to it being closer to the forefront of our minds, then I count that as a success.

AC: Have you been in touch with any of the people you interviewed since filming?

BK: A couple of soldiers that I befriended in the process of filming. Even when I had all of their interviews done, I continued to go back and see them, visit them, check in on them. And sometimes we would just hang out, so I became friendly with quite a few of them. So every once in a while we text; I check in to see how they’re doing. That’s kind of how I know how their injuries have been, because some of them have had to get multiple surgeries even now, two years later, three years later.

Editor’s note: This interview was done in early September of 2023, and the following questions reflect the situation at that time. Although the current situation is different, we still believe that this part of the conversation has relevance for our community today.

AC: Are any of them still in Artsakh?

BK: Most of the soldiers were not from Artsakh so they’re back home in their villages or in Yerevan. The ones who are in Artsakh, I’m not sure. They’re the ones who have been difficult to get ahold of.

AC: One of the lines that really stood out to me in the ending says, “This war is happening today.” Which is true now more than ever. How do you think that the meaning and importance of the film have developed as the situation in Artsakh has changed?

BK: I think that it’s kind of become an important piece of context to what’s going on. To be honest, I was a little bit nervous when I released it because I thought, man, so much has happened since the war; the war is not the most recent tragedy that’s been going on. Does anyone even care to understand that stuff now?

But what I realized based on people’s feedback was that the stories of the people that went through that stuff have some similarities to what people are going through now. It’s not the same situation, but the fear that people feel and the threat of death and destruction is very much similar to what it was then. They’re still living in fear, they still don’t know what the future holds. And that’s something I think that was very poignant about what the Artsakhtsi mother said. She was saying “We don’t know what the future will hold, but this is our soil and we’re not gonna leave.” That is something that still applies today. Even though the situation has changed a lot, I think it’s still their attitude that they’re not gonna leave, they’re gonna hold their ground and show their strength.

So in a way, it’s like the meaning of the film evolves as the events play out. But I don’t want to sound so highbrow about that, because it was not my intention. I would love it if the film became meaningless because everything ended and people were safe. But unfortunately, this is just the situation and I think that the feelings that were expressed by the people I interviewed in the documentary are very similar, if not the same, to the feelings of people that have seen – not just in Artsakh but also in Syunik, in Gegharkunik, in the border regions – it’s still very tense all the time.

AC: From your work and your connections with the people in the film, is there anything you think people aren’t hearing about that needs to be talked about?

BK: I think the recent buildup of equipment on the border and soldiers by Azerbaijan is definitely concerning. I think the reality of another attack happening is not lost on many people – definitely not people here. I think more people should know that the war didn’t end. Even a peace agreement is not an armistice, it’s not a treaty. It’s a ceasefire essentially and it’s not one that’s been very effective – it’s been broken plenty of times. So at the risk of sounding grim, I do think that the reality of the situation does need to be paid attention to, that we’re probably gonna be attacked again, and we need to be ready and figure out our solutions quickly and work together. And I don’t have the answers, honestly, but I’m here to help however I can.

AC: I don’t think any one person has the answers, but at least having these discussions and thinking about it is a step forward. Is there anything else you want to talk about or that we missed?

BK: Please go watch the film, please share it, and let’s keep these kinds of conversations relevant to the non-Armenians as well. And not just mine, go watch Ghosts of Karabakh by Popular Front, that’s a great short documentary that was filmed after the war as well. Keep your ear to the ground. Double-check your media sources. This goes for everything, not just Armenia. Be informed. Knowledge is power. Information is the key to a freer world.